AI Might Come for Your Job — But Human Skills Could Save Your Career

As AI continues to permeate the technology we use on a daily basis, urgent questions arise about our collective future. Which jobs — or even entire fields — will become obsolete? How can students develop robust critical thinking skills when computers can do their schoolwork? And what role do human qualities like empathy, courage, and leadership play in a world shaped by AI?

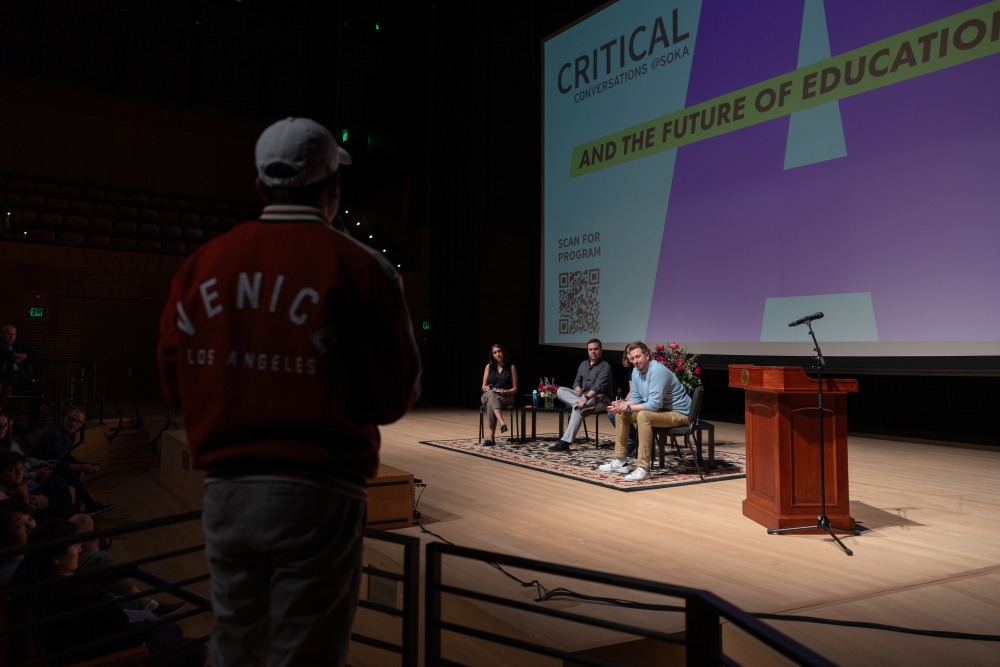

On Nov. 7, the SUA community and general public gathered to hear experts discuss these questions at Critical Conversations @Soka: AI and the Future of Education and Work. The panel featured Hilary Mason, data scientist and CEO of Hidden Door, as well as Casey Newton and Kevin Roose, cohosts of The New York Times tech podcast Hard Fork. Moderated by journalist and SUA alumna Jihii Jolly ’11, the conversation was followed by a thought-provoking Q&A session addressing questions from SUA undergraduates and local high school students.

Making Sense of the Benefits and Risks of AI

Jolly kicked off the conversation by asking the panelists to give the audience an overview of the current landscape in the field of AI. In under two minutes, Roose delivered an impressive “capsule history” outlining the advancements in machine learning and neural network architecture that underpinned the generative AI technology discussed by the panel that evening.

“Now we have AI that can write essays and songs,” Roose said. “It can make movies and generate podcasts … All of this is getting cheaper and more accurate.”

But the large language models used in AI have not yet surpassed the intelligence of a human being, Newton explained. When an AI model can’t solve a problem, it will provide inaccurate information, known as a “hallucination” within the tech industry. Furthermore, because of the way these models are designed to favor statistical averages, the content they produce is often of average quality.

The current limitations of AI, Mason stressed, are important to keep in mind when determining uses for these powerful models. Tools like GitHub Copilot are extremely useful in helping computer programmers write tried-and-true code, for example, but they’re not yet good at creative architecture and complex system design.

Even so, Mason said, “There are tremendous applications in medicine and science. We can now spot patterns too subtle for the human mind to be able to recognize and see their statistical significance across an amount of data that is too vast for us to conceive of. And then take that vastness and reduce it to something we can understand.”

However, these benefits come with risks. “When you take an automated system,” Mason said, “and have it make decisions potentially millions of times a minute, if that decision is even a tiny bit biased or wrong, that will be scaled … All of the biases of humanity get magnified because of biases in the training data.”

Newton worries about the harm technology like a nationwide facial recognition system could cause. “I pay very close attention to new capabilities that arise in AI,” he said. “The minute one arrives, you have to ask yourself, ‘What would be the worst use of this technology, and is there a meaningful way to prevent that?’”

“Everyone Gets a Personalized Tutor”: AI and Education

Having painted this nuanced picture of AI today, the panel then discussed the implications of AI for the future of education. Mason argued that it’s not realistic for educational institutions to expect students not to use AI to assist with their schoolwork when they use it all the time outside of school. Instead, she posited, we must create an environment where educators can guide students in how and when to use the AI tools available to them, while also setting reasonable limits and consequences. “We need to teach people about integrity in a way that also sets them up for excellence,” she said.

For example, when using generative technology for writing, Newton said, “AI is a starting point, not an end point.” Roose agreed, explaining how having ChatGPT summarize a text or provide the 10 main points on a topic are great ways to get an overview and find areas to research further. As a writer, Roose often uses ChatGPT as his personal critic, asking it to find the strongest counterarguments to what he has written so he can sharpen his own assertions. Education, the panelists argued, should include opportunities for students to develop these skills so that they are adequately prepared to use AI effectively and responsibly throughout their academic and professional careers.

“We’re very close to having a world,” Roose said, “where everyone gets a personalized tutor in their pocket that can meet them at their exact level of understanding … That is a superpower for technology that we should be pushing.”

Human Skills for a Shifting Job Market

In the area of employment, the automation of tasks that were historically assigned to recent graduates has raised the floor for entry-level skills, a trend that the panelists expect to continue. To bolster their readiness to enter the workforce, the panelists recommended that students hone their uniquely human skills, like the ability to collaborate with other human beings, especially across different functions.

“A lot of early AI rollouts are going to be siloed, narrow applications,” Newton said. “If you’re someone who can work across teams and who is really good at communicating, you’re going to have an advantage.” These skills, Roose added, are more easily acquired working in person than remotely, especially for those just starting their careers.

A true creative sensibility, Roose argued, is another skill set that distinguishes human workers from machines. Because AI models pull together statistical averages, they are not equipped to identify excellence and originality. He worries that the way algorithms cause users to drift toward whatever is most popular — for example, the way Spotify recommendations may lead millions of users to the same music — might flatten taste on a mass scale to the point where, Roose said, “we let go of our agency and desires, we stop knowing what’s interesting to us, and we end up in a very boring world.” Developing a unique palate and nourishing a genuine sense of curiosity, therefore, are other crucial ways young professionals can offer value that surpasses the limitations of AI.

In a similar vein, Mason emphasized the importance of developing good judgement and a sense of when to take risks. “An automated system won’t tell you when to subvert the rules versus when to follow them,” she said. “You have to know when to do something different.” The ability to take risks and go against expectations is fundamental to entrepreneurship and to solving problems in a wide range of fields.

Roose recommended developing qualities like empathy, courage, ethics, and leadership, which will help young professionals build relationships and become strong communicators and team leaders. While these critical skills are seldom taught beyond middle school in most educational settings, they are central to the values-driven education students receive at SUA. Here, students gain daily practice building the kinds of human skills that Roose believes will help workers “future-proof” themselves in a rapidly changing job market.

As the capabilities of AI continue to expand, Newton suggested taking some time every few months to familiarize yourself with what AI can do in your field of work. “If you do that,” he said, “you’re going to have a better sense of how AI is improving in real time, and you can use that to guide areas of your profession where there is still more value that can be created by humans.”

Although developments in AI and its implications for the future can feel overwhelming, the panelists were ultimately hopeful for what it all means for young people entering the workforce in the next few years.

“The job market is changing,” Mason said. “That can be scary, but it can also create a lot of opportunity. And that can be really exciting. It’s both at the same time.”