Civil Rights Leader Whitney Young’s Fight for the Soul of America

In 2013, to mark the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington, Michelle Obama held a White House screening of The Powerbroker: Whitney Young’s Fight for Civil Rights. She described the documentary as an opportunity to understand how much work goes into creating change, and called Young an unsung hero. The then First Lady also asked the audience to think about how each of them could become agents of change.

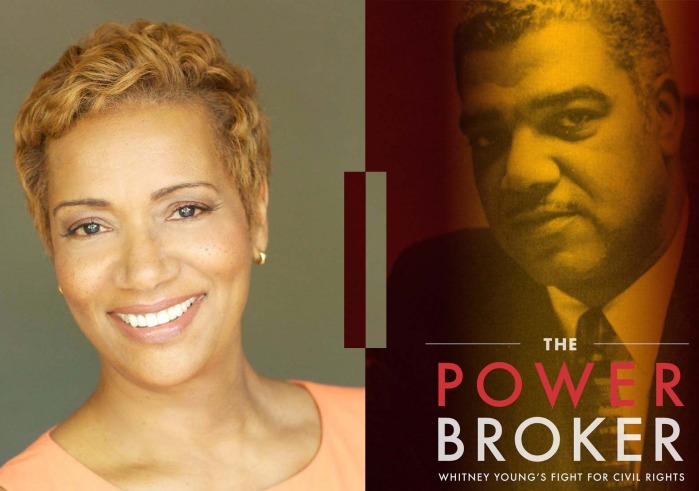

In introducing the film to members of the SUA community gathered online to commemorate Martin Luther King Jr. Day, Professor of Latin American Studies Ian Olivo Read suggested they ask themselves the same question. That sentiment was echoed by Bonnie Boswell, the award-winning broadcast journalist and Young’s niece, during the discussion following the film.

“This acclaimed and remarkable film documents Whitney Young’s extraordinary story, as the man in the middle between white and Black, rich and poor, during one of the most turbulent times in American history,” said Read. “Despite becoming a target of intense criticism from both white people and the Black power movement, Young helped erase African American stereotypes and opened opportunities for minorities that continue to influence diversity in America today.”

During the Q&A session following the film, Boswell, currently the executive producer of Bonnie Boswell Reports on PBS, touched on Young’s place in the civil rights movement, his legacy, and her personal relationship with her uncle. Her first memory of him, she said, was when she was about six years old and visited his home in another state. He continued to reach out to her throughout his life.

Boswell described the relationship between her uncle and MLK not only as partners and collaborators in the movement, but as family. “People understood and respected that everybody had a different role to play–Martin Luther King was in the pulpit and Whitney Young was in the boardrooms and Dorothy Height was taking care of communicating to women,” said Boswell. “They didn’t always get along like families don’t, but there was love, there was respect. And there was the idea that just like the parts of a watch, you need every single part to make the whole thing work.”

Young was a social worker, and he brought that perspective to his work in the movement. He saw his role, Boswell said, as keeping people at the table.

Virtues in Action

SUA Vice President of Mission Integration Kevin Moncrief, who co-moderated the discussion with Manager for Diversity Initiatives and Community Building Maya Gunaseharan, asked Boswell how Young and King exhibited SUA’s foundational qualities of wisdom, courage, and compassion.

Boswell quoted both men regarding those virtues. Young, for example, said that “Every man is our brother, and every man’s burden is our own. Where poverty exists, all are poor. Where hate flourishes, all are corrupted. Where injustice rings, all are unequal.”

That statement, Boswell said, encapsulated the movement leaders’ understanding of the interconnectedness of life. What we call the civil rights movement was “broader than just going from one part of the bus to the next,” she said, “it was about saving the soul of America.”

“It is not a Black thing but an injustice thing, and so we have to really go broader than just seeing things on a skin-tone level, or gender level, but really on a basis of fairness and justice,” Boswell said. “That was kind of critical to both of their ways of thinking.”

Both men exemplified courage by going “into the breach,” during a time in history that was extremely fractured and divisive. Young and King grew up at a point when Black people couldn’t eat in any restaurant they wanted to, for example. Boswell said Young knew he wasn’t always going to be liked, but thought the most important thing was to get something done.

Boswell referred to MLK’s imaginative empathy as indicative of his compassion, as seen in his hopeful statement: “I believe that unarmed truth and unconditional love will have the final word.” Young, too, needed to call upon that quality to help him interpret Black power “in a way that the threatened white community could embrace it.”

“Young said, ‘Black power simply means look at me,’ ” she said. “‘I’m here, I have dignity, I have pride, I have roots. I insist, I demand that I participate in those decisions that affect my life and the lives of my children. It means that I am somebody.’”

In response to a question about what advice she’d offer SUA students, Boswell said the first step is for them to become educated citizens. “Education is critical to being able to develop a compassionate population,” she said. Without it, people can easily become biased and constructive dialogue is impossible.

Boswell said it was important for Americans to “really get involved in the spirit of the country,” and advocate for the things that most speak to their hearts. “We have a mission that each of us can do uniquely,” she said. “Whitney Young and Martin Luther King were able to go from the world they grew up in to moving the ball forward, so they’ve handed this off to us, to you.”