Soka Launches New Life Sciences Concentration

Soka University of America is officially opening its Life Sciences concentration this fall, offering a unique, research-based science program for undergraduate liberal arts students.

Life Sciences at Soka is flexible, the curriculum designed to give students the opportunity to plan their own path. Are you pre-med? Interested in biological fieldwork? Molecular chemistry? Physical therapy? Soka can take you there.

And because Soka is starting from scratch, said Susan Walsh, director of the concentration and associate professor of molecular/cell biology, the university has been able to develop a curriculum that teaches core scientific concepts in an efficient and compact way.

“We get to think about what students really need,” Walsh said. “And we built all of our learning objectives in conjunction with our assessment, so that we can really have that opportunity to say ‘OK, this is what we want graduates to walk out with.’ ”

The science classes are complemented by Soka’s expansive liberal arts offerings and the school’s focus on encouraging global citizenship. Students should leave the program with a humanistic perspective and be as adept at explaining science as they are at practicing it.

“It’s not at all a traditional science program,” Walsh said. “We are a liberal arts school and that’s great, because they’ll have the science knowledge that will hopefully help them interpret and understand things like a global pandemic better than the average citizen.”

Starting a new concentration during a pandemic isn’t without challenges. Because all fall instruction will be online, students will have to wait to use the teaching laboratories in the new science building, the 91,000-square-foot Marie and Pierre Curie Hall.

Meanwhile, Life Science faculty have adjusted, using the fall to set the stage for experiments when students are able to return to campus. In one independent study class Walsh is teaching, four students are each picking a yeast gene and, using a suite of computerized bioinformatic tools, are designing experiments to predict how it will behave. It’s the kind of hands-on research that Soka is emphasizing in the concentration.

“Rather than walking into a lab and seeing how enzymes work and doing what is already known,” Walsh said, “let’s come up with a novel problem and actually do the science to figure it out.”

Soka is welcoming 23 first-year students into the Life Science concentration this month, joining approximately the same number of rising sophomores who started taking chemistry and biology courses in the 2019-2020 academic year.

To fulfill concentration requirements, students will take two foundational courses in chemistry and biology, the latter being co-taught by a biologist and chemist to help students understand the cellular hallmarks of cancer. In addition, they will have two associated laboratory courses in which they will design and complete research projects, and another project-based lab course. Given small class sizes, students will always have specialized attention.

Walsh, and the other eight professors in the concentration, designed the curriculum for flexibility while also fulfilling national guidelines for undergraduate science education. It’s also set up to prepare students for the post-graduate paths they hope to pursue in medical health, applied research, biotechnology, and beyond.

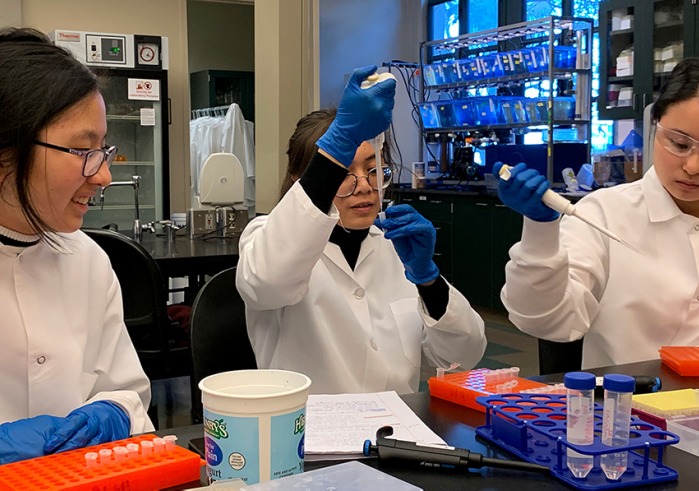

All Soka Life Science students will spend a significant amount of time in the laboratory, which, in many undergraduate science programs, is optional, not required.

“Our students are going to be super well-prepared to go into a laboratory,” Walsh said, “be that a graduate school laboratory, a government laboratory, biotech, or pharma, to do summer internships.”

This summer for example, students anticipated doing research in Singapore, Japan, New York, San Francisco, and on campus with SUA faculty, before plans were interrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Fittingly, Soka students have made resourceful adjustments. Two have become certified contact tracers in the fight against COVID-19; another got a summer job working in a clinical lab at UC Irvine Medical Center.

Rising sophomore Reika Nyunoya was ready to present research in San Diego in April before the pandemic. Instead, Walsh invited her to take her place for an online poster session organized by the American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. Other presenters included graduate students, post-docs and professors. Nyunoya fielded questions on a poster she and other first-year students worked on with Walsh: Genetics in Action: Mutation of Chromoproteins in First-Semester Introductory Biology.

“It was a great experience,” Nyunoya said.

Other now-second-year students got a taste of hands-on research on campus last academic year. The experience was immersive and engaging and began with their first classes. Saanika Joshi, a rising sophomore who hopes to become a doctor, worked on research project on mutating biofluorescent chromoproteins, learning about data gathering and entry, issues with faulty data, and shortcomings of the experiment as a whole. In her second semester, Joshi worked on harvesting and analyzing DNA from genetic samples from Southern California coastal zones, collected by marine biology students in another class, to see if there is genetic flow between populations.

Mikey Venezia ’23 appreciates the personal relationship he has with Life Science professors. Venezia, who was recruited to play soccer at SUA, hopes to combine his passion for sports and medicine and become a chiropractor or physical therapist. He wants to provide the kind of supportive and empathetic care that he felt was lacking when he was recovering from athletic injuries in high school.

“Stuff like that can really change your life,” he said. “I think a liberal arts education can help me learn the science, but you also learn the ethical side of how healthcare affects humanity. Not just straight science facts but also taking into account sentiment and empathy.”

Like Venezia, an increasing number of students are interested in careers in medical and affiliated health careers. And SUA’s approach to science has already changed the perspective of students like Joshi, who is excited by how a liberal arts education can help her in her medical career.

“You’re forced to look deeper into the ethics and psychology and actual human behaviors and connections with people that you make,” she said. “That’s a big part of going into the medical field. You have to interact with people and so anything you can do to better understand those people ultimately helps how you end up treating them.”

The program is practical and hands on, yet students are also required to complete Soka’s core curriculum, which covers elements of philosophy, history, writing, and other liberal arts courses. The science training is augmented by a foundation in critical thinking, effective communication, and understanding of how to create social value.

For Joshi the Soka spirit was reinforced during a Learning Cluster class trip to Scandinavia last winter to study the Norwegian model of outdoor education. Witnessing the model’s benefit to children’s health gave her another perspective on how lifestyle and policy can influence healthcare and how people should be treated.

“And that’s more of a reason for me to go into medicine, to help people who maybe don’t have the opportunity to think about this stuff,” Joshi said. “The same with racial disparities in medicine: how can I as an individual work to eradicate those wherever I go?”