Indigenous Communities Retaining their Traditional Fishing Right in the CNP (1990s) by Subina Thapaliya '22

Environmental Movement (EMP340)

Blog1_Subina

03/15/2021

Indigenous Communities—Botes, Majis, and Musahars—Retaining their Traditional Fishing Right in the Chitwan National Park in the 1990s

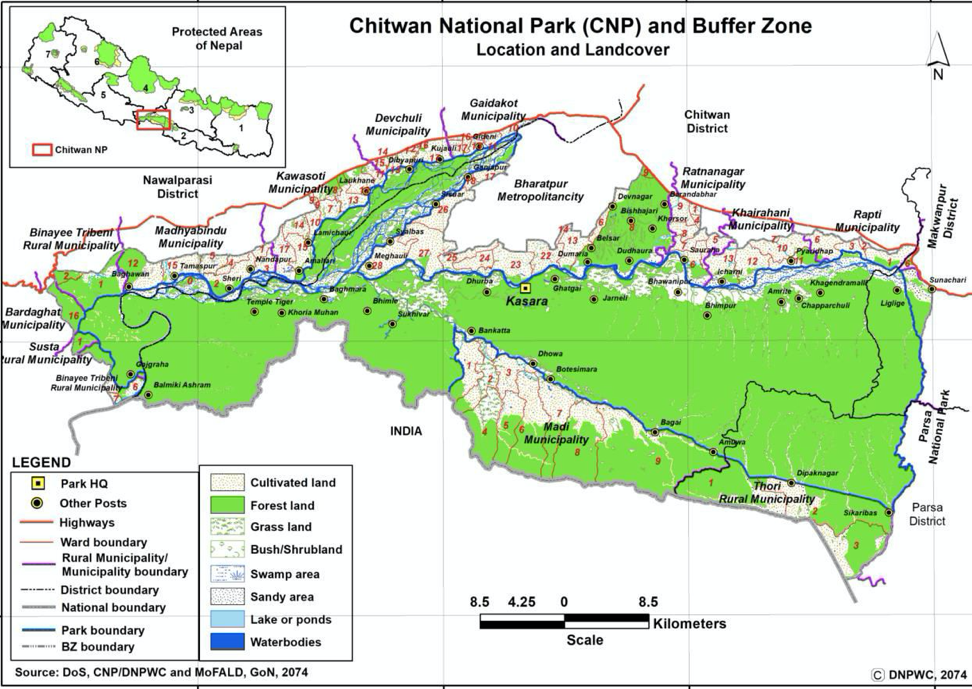

Growing up in a village located in the periphery of Chitwan National Park Buffer Zone Area, I heard two different narratives of Chitwan National Park (CNP). One narrative portrays CNP as Nepal’s pride, which has been enlisted in world heritage site by United Nations Educational, Scientific, Cultural Organization (UNESCO) for its rich biodiversity. Unlike the first narrative that widely dominates the academic world and media both at the national and international level, the other narrative is restricted chiefly at the local level. This second narrative portrays the CNP as an obstacle to livelihood for local people who depend on natural resources for their survival. I know incidences where the security personnel deployed in the CNP had physically and verbally harassed people in my village even when they went to the forest with an official permit. These hardships of the local people added by the park conservation policies and regulations have rarely been discussed beyond the local setting. This blog summarizes one of those obstacles faced by the indigenous fishing communities—Botes, Majis, and Musahars—and their successful environmental justice movement that retains their traditional fishing rights in the 1990s. This case study was conducted by International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD), and the blog summarizes their book published in 2007 (Jana, 2007).

Following the establishment of CNP in 1973 AD, the CNP regulation act was made in 1974. The conservation policies and practices made under this act restricted fishing in rivers and watersheds around the CNP. This policy adversely affected the Botes, Majhi, Musahars, and other indigenous fishing communities whose livelihood entirely relies on fishing and ferrying.

Suddenly, the sources of livelihood for local people such as fishing, gathering wild fruits and vegetables, grazing livestock in the forest became illegal. The Royal Nepal Army’s deployment (now Nepal Army) in 1975 for the law enforcement of biodiversity conservation in CNP further exacerbated the hardship of these indigenous communities. The Army abused the local people verbally and physically as well as terrorized them into doing involuntary works. Women became the victim of sexual harassment and rape. According to the villagers, there were many children born from rape cases. More than 30 women claimed their children being born by rape from security personnel of the CNP in seven buffer zone village development committees.

In defense of the violation of their human rights and restriction to access their traditional livelihood sources, the indigenous people started the resistance movement in 1983/84. In 1986 to suppress the rising voice of the indigenous people, the national park authorities issued arrest warrants against the leaders of this activists’ group. The leaders had to leave their homes and hide in the forest. Eventually, after the national park authorities’ atrocities in February 1993, in which they confiscated boats and fishing nets from the local people and burned their belongings, the indigenous groups held their first official convention. In 1994, they registered an organization called Majhi Musahar Bote Kalyan Sewa Samiti (MMBKSS). The organization addressed the royal palace (this was post-democracy in Nepal) with an appeal for restoration of their fishing right and to address the issue of harassment from the Army and park authorities.

The royal palace addressed their appeal, and leaders came back with a six months license to fish. However, this action was short-term, and the indigenous communities again started being harassed by the Army officials and park authorities. The park authorities placed fishing restrictions, and they stopped issuing the fishing license. The fishing communities again stood for their rights and planned for a campaign named Kasara campaign. They approached leaders from political parties and representatives of the district development committee, local government, and the media for additional support. On August 20, 1999, about 900 people protested at the Kasara post, which is the headquarter office of the CNP, with the slogan “Macha marney license paunu parcha! Saag sabji, niuro launa dinu parcha! Sahi sainik ko atanka banda gara! (We should be given fishing licenses! We should be allowed to gather wild vegetables!

Stop army violence!)” This demonstration paid off as the Warden, the chief officer of the CNP, asked the protestors to come back the following day to get their fishing license, issued in tenure of six months. He declared that even women from the communities could get the license.

Along with retaining their social and economic security snatched away by the CNP rules, Majhi Musahar Bote Kalyan Sewa Samiti (MMBKSS) worked to uplift the lives of the indigenous communities through the establishment of the school, water pipes and tube wells, embankments across the settlement to prevent flooding. The CNP also started allocating part of their revenue towards the upliftment of the local community via the Buffer Zone User Committee. Unfortunately, over the time, the environmental justice movement of MMBKSS faded away due to internal discord among leaders and the intervention of their work by the third party i.e., the national and international non-governmental organizations who started working around the environmental justice issues in the CNP.

It took more than three decades for Bote, Majhi, and Musahar communities to restore their fishing rights. Even two decades after their successful movement, many conflicts between the local people’s well-being and conservation policies still surround the CNP. The harassment of the security personnel to the local community still exists (Ghale, 2017). Just a couple of days ago I shared about this blog project to my brother who is back home in Chitwan. He responded, “A few days ago a boy from our village who went for fishing in the Rapti river [the river within

Chitwan National Park Buffer Zone area] got beaten to the death by the Army [deployed by the CNP].” It is time we talk more about the national park’s second narrative, even outside the local setting, to make the park management committee responsible for the consequences of their actions and operations. The park must ensure the local people’s safety and security while working towards the conservation of the One Horned Rhinoceros, Royal Bengal Tiger, and Gharial Crocodile. They cannot violate human rights and rights of indigenous people over their land and resources while working towards the preservation of ecology and biodiversity.

References

Ghale, S. (2017, May 1). The dark side of Nepal’s national parks. The Record. Retrieved from https://www.recordnepal.com/art-letter/books/the-dark-side-of-nepals-na…

Jana, S. (2007). Working towards environmental justice: an indigenous fishing minority’s movement in Chitwan National Park, Nepal. International Center for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD): Kathmandu.

Index